|

The artist sometimes deliberately chooses to confine himself to the sheet of paper and pencil. He will thus draw grey or black outlines with a simple schoolchild tool on a virgin page. If he were to be questioned, maybe he would admit that the sensual pleasure of gliding the pencil over the bristol board prevails over that of giving birth to the sons and daughters of his dreams. Instead of being an obstacle, the immaculate bristol board is an invitation, a temptation, the promise of a real delight. The artist will dive into this plain surface as into a water that conceals under its extent a fruitful bubbling. He can then concentrate his efforts to achieve the completion of a gestation, germination, a birthing process, and thus reveal the complexity of his intimate mythology… These resources are so limited that he knows he masters them fully. He is the master of the stroke, of the surfaces and shadows. This apparently sterile surface will be the scene of a spontaneous generation.

It is going to raise itself from reliefs, nuance itself through shadow and light and become as lively as skin. This medium, free from any presence, will be rubbed with pencil by a thaumaturgist’s hand and reveal to us the invisible. |

|

|

|

|

Duc knows all of the resources offered by that technique. He knows how to vary the line, from the firm, sharply drawn stroke to the light trace that barely grazes. He knows how to outline the whites with greys, giving them a different light than that of the background. He can suggest a volume by a mere outline, just by strengthening or lightening the stroke. He draws shadows in which other shadows open depths. He gives birth to thicknesses that seem to be taken from the paper substrate itself. It looks as if cut out, sliced as in a rind, unveiling the organs it covers. He annexes little by little the surrounding by means of hatch patterns which turn out to be grass, human hair, animal coats... Indistinct shapes go through still intact areas with a light texture that the eye, beyond, guesses other appearances ready to lift that thin film and materialize on its surface. Ducs graphics are drawn with extreme delicacy. He makes use of the different intensities of grey: dots, hatches, nervures, folds that attract attention to a flat extent, underline a volume, animate a surface. They offer the spirit a diversion comparable to that of a grace note or a variation in a musical theme. And this applies up to the ultimate touch: his English-style signature with his D coiled like a snail shell.

However, this know-how, so attractive to the viewer, so important to the artist, is not the main thing. If drawing and painting are arts and not crafts, the reason is that, using the same resources, they are not on the same level. If the createur does not use his or her talent to serve an original reflexion, a new world, if he or she does not reveal an original spirit, he or she cannot take a place among the artists. Dexterity is indissociable from art, but it cannot replace it.

Duc’s imaginary is of extraordinary richness. He possesses in himself an endless catalogue of images. The shapes seem to occur effortless in his brain. They are crowding, ready to appear as soon as his hand reaches the paper. The place where the pencil lands is instantly fertilized. The lines become rounder, interlaced, the surfaces spread out, are superimposed and creatures come alive. There seems to be a huge number of those protean creatures. They are animated with a life the purposes of which we cannot guess.

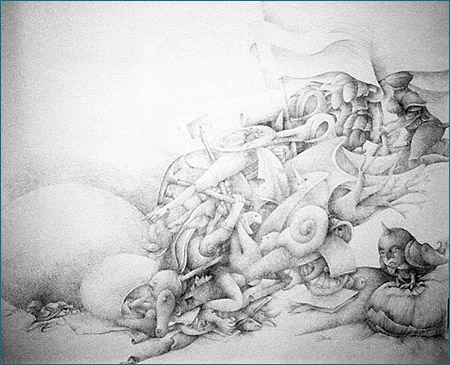

It is hard indeed, at first sight, to discern the subject of these drawings. They abound in man’s and nature’s productions. They provide a puzzle of animals, plants, objects and characters the meaning of which escapes the first sight. In fact, the primary goal of these constructions is the organic viability of the whole. All these things, whose elements are intermingled, had to build up a coherent mass and make that kind of Meccano containing a large number of disparate parts appear to work.

First, one can attempt to sort out these drawings according to theme. Then identify the characters, the things the artist represents most of the time. These themes are those in the mind of any artist, any person that haunt and fertilize the imagination: the woman, the movements of love and desire, the objects, the animals, the plants, the landscapes... You have to know how to follow them from one drawing to the other, get acquainted with their metamorphoses and grasp their hidden meanings. In particular, it is necessary to consider each work as a whole and attempt to understand how that crowd of representations is assembled, how they develop in the space and which breath animates them.

The woman created by Duc is not a portrait, but a symbolic woman, the medium of his tender or erotic dreamings: the delicate traits, the narrow nose, the long and oblique eye, her face is shown from the side, dreaming and impassive in the center of the scenery. Her hand with her fingers raised like those of a sacred dancer turns into petals, feathers, or a fowl leg. The joint of the arm has the softness of a rag doll. She has the elegant haunch of a mare or doe. Her fine leg, often articulated as that of a marionnette, ends with claws or a hoof. The women’s bodies are full, their stomach and breast round. The groin, the elbow crook, the knee hollow and the navel are represented with sensitivity, as is the split sex below the child’s pubis. The woman can also be a nourishing goddess. A whole vegetable or marine life develops in her hair: leaves, branches full of fruit, flexible antennas, undulating stems, half-living heaps from which sea anemon tentacles stretch out, with, on their surface, pearly bubbles transforming into calcareous concretions.

|

|

|

|

The bodies mime all the acts of love. They intertwine for hugs into which extra limbs are sometimes mixed.

Some isolated parts of the body are limited to a single gesture, a specific stroke: open mouths seeking some flesh to kiss or bite, fellatio, stinged tongue, breast grabbed by a hand or snapped up by a jaw, thigh clasped againt another thigh, buttocks or stomachs squeezed against the rump of a horse or a stag. All these beings are mixed, intermingled, united in silent Bacchanalia. It is a universal glorification of Eros. Not only mate the humans, the snake swallows a phallus, the tree bears an erect branch, the bird pecked at offered lips... male and female sexes are detailed with a complacent minutia. These voluptuous vibrations extend across the thickness of a petal, the winding of cloth, the joint of a leaf, represented with the same sensuality as the folds of a living body.

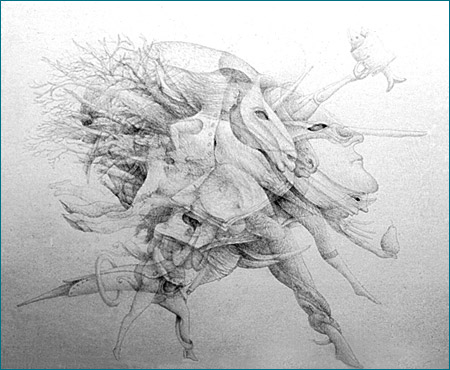

Duc is also sensitive to the male erotic force of certain animals: rhinoceros with a phallic horn, strong-limbed horses, powerful unicorns, athletic cervids naked in their fur. Assertion of virility also appears in these helmeted warriors, covered with armor, brandishing their spears, with gestures of brutal possession and in these faunistic trees with strong erected tree trunks pointing towards the heavens. |

|

This erotism sometimes verges on perversity. The flesh is often pierced, cut off, squeezed by ties that make it swell. There are sharp beaks, claws, mouths full of teeth, horns that burst through foreheads, run through limbs, mechanisms that evoke instruments of torture. These sensitive bodies that seek pleasure do not escape the fear of what can injure or mutilate.

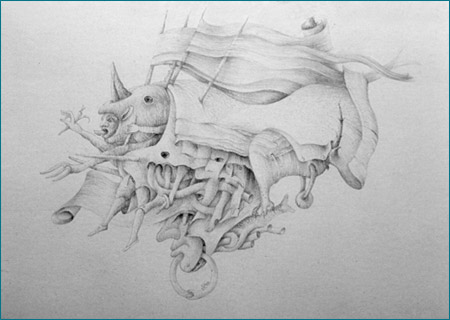

A large number of characters are only captured looks, surprised gestures, hints of movement. They ogle through the unbuttoned slit of a coat. They suddenly appear in a gap of bark, in a hollow of the ground. They stretch a hand, an arm, under a book, a section of wall, a shell valve. Hidden in order to see, they seem to be born from a fold of the ground, appear like snails from a vegetable or organic heap. They are sometimes reduced to a single eye, the painter’s eye, the voyeur’s eye, seized by even that which he observes.

Duc details the animals as a naturalist. He noted carefully each of their specific characteristics. He knows how to caress from the reflection of human tenderness the familiar cat, the loyal dog, the fowl or the pet pigeon. He also represents the fish like hands stealthly gliding through the water, scaly flesh, wave-like motions scarcely materialized in water. The bird flying high up above reveals the lightness of the sky. The egg, intact or cracked, the symbol of every hatching. The snake that crawls and coils, the owl which looks humanely, the sheep, the tender throat offered where the knife will enter. These animals can also express the fear we have of them, of their claws, of their teeth, of the danger of their deeply-rooted animality. They take the form of the mythological creatures that they provoke: centaurs, harpies, wolflings, bird women, sirens, all a fantastic bestiary to which the painter adds his own chimaeras.

He also annexes the world of man’s industry. That of the objects used in everyday life, as close and loyal as tame animals: the book, the sheet of paper, the fork and the knife, the watch, the clock. There are tools, those of the craftsman, the farmer, the handyman: the hammer, the rake, the ladder... their representation adds straight lines, edges and corners amidst more organic constructions. They also carry a hidden meaning, the spiked fork, the aggressive knife, the companion book, the waiting window, the messanger envelope... The spirit that has chosen them has first vested them with a weight of meaning. The hand that draws them has stroked and weighted them to give them his trademark. Each element has been transmitted the DNA signature of its creator. |

|

|

There are also representations halfway between the organic and the man-made: pipes that look like intestines, œsophagus, sexes, bags that could digest just like stomachs. Inert objects that only ask to turn into living organs and replace viscera or prolong an animal or human limb. Some beings are cyborgs: made up of both flesh and mechanical parts. They are tightly nested in utensils from which we could not remove them without threatening their viability. They are made of wood, iron or fabric tissu. Each material seems to have been worked on with its own specificities. The wood is carved, pegged, the metal is nailed, riveted, bent. The fabrics are pierced by eyelets, buttonholes, strapped up with leather, strings. The paper creases, folds or rolls up. Some characters happen to become part of vegetable parts that also seem to be ready take on organic functions. The artist has the power to represente the living and non-living things without establishing any frontiers between them. He does not forget to include the bolts, the nails, the screws and the whole system made up of metal parts... As the connecting rods and the gear wheels, the holders of this fascinating machinery which finds its achievement in the engine, a living and beating organ, as advanced as a heart.

|

|

There is, in Duc'sdrawings, such an outpouring of ideas, themes and representations. The perspectives that he unveils are so diverse it makes it difficult to fully figure out his mental landscape. The creatures that live there, the aventures and metamorphoses that affect them seem to be, at first sight, as varied as undecipherable. However, one can attempt to go back to the movement that has given them birth, to that kind of impetus that started from the artist’s entrails themselves, asking to incarnate them externally. This drive, this first manifestation of the desire to create, translates into a breath which animates his compositions and underscores them. It is materialized by spirals, torsions, flights, more or less tight matter conglomerations. Each work, like a plant, has had its own particular growth. Each of them proposes an interpretation of the dynamics of the living. The beings and the objects which accompany these great movements are there like condensations of substance and meaning.

Some drawings were built up from a central mass, a block, a magnetic meteorite, a gangue in which human and animal creatures are caught in. Other coil up into a spiral which drives a whirlwing of beings and objects. Duc sometimes amalgamates into a compact group a number of figures that levitate over the horizon. The group is sometimes less dense and the air flows through as though a swarm of insects or a flock of birds. All around floats a flight of wings, fabrics and flags. Some compositions force themselves out from earth in a powerful movement, others seem to glide just close to the ground, with legs running, wheels turning, lifting a vast number of objects. He can create a work by agglutination, as in cultivation of organic material, or by choosing to cover the whole of the page with assemblies, successive stacks where each shape generates the next one, molding itself tightly onto it. Because Duc possesses in himself everything he needs to create and his vast plastic vocabulary is contained in his memory, he can join his interior movements to them. He is never stopped by the necessity to check around for the appearence of an object, an animal or an anatomic structure. Because he uses it with both the naturalist knowledge and the intimate knowledge he has of it. He can use reality without bothering to reproduce it in its restrictive exactitude.

Drawing is a thought expressed by means of the image. Yet nobody, not even the creator, could have imagined the aspect it would take until it came into existence as a result of a few strokes. This creation is not "thought", "imagined in advance". It comes to light as it is drawn. The simplicity of the medium used allows the artist to to dive into the "alert" state required by giving birth to a work. From the very first mark drawn on the paper, he will find himself in the situation of an individual who, in gestational state, would have the power to operate on his embryo, whereby the latter is not passive. There is constant interaction between the creature and the one who gives birth to it. Às it appears, it sends messages that will lead its own genesis. The painter possesses a vocabulary which is not made up of words but visual representations. From the moment he has opened his eyes, they have imprinted in himself.

They may reflect as much of his culture and personal history as that which can be written by the writer or told by the speaker.

For him, the shapes and colors do not need to bear a signification to have a meaning. He will draw his ideas and feelings from his plastic catalogue. The usefulness of things does not reside in the use one can make of them but in the emotive power they conceal. But saying the drawer or the painter thinks with images does not mean he will renonce his intelligence. Art is not only a reserve of emotions, but the result of reflection.

But the latter is not of analytical nature, it is somehow global. Other creatures are also able to understand the world depending on the position they have in it. An insecte thinks as an insect, the bird as a bird. They know how to adapt to their specific space and identify all the essentials to their survival. The artist, for his part, thinks as an artist; he knows how to extract from the creation all the elements which will allow him to carry out his task. He has the desire and possibility to recompose the information about it in order to create the only world which would be, to himself, an inhabitable world. That world possesses its rules and laws; it is different from all the others although its author has used things that are known to everyone in order to build it. The viewer must get into his universe with no preconceptions and understand message.

The viewer must accept the shapes to communicate with their inner self and breathe into them some breath of emotions, a range of feelings and ideas he can perceive directly, without the help of words. |

|

| top |

|

|